If we can’t save the most iconic species of all, what hope is there to save pangolins and other endangered species?

With just 3,900 wild tigers in the world, Save Wild Tigers' founder explains how we've arrived at this critical point and how we can ensure wild tigers are still around for the next Year of the Tiger.

When I was five or six years old, I was given a toy tiger who I fell in love with at first sight and who accompanied me everywhere and I mean everywhere. He was coiled round in a lying position, a position I assumed was especially made for fitting around my hip to carry him around.

Tiger was often wrestled from me by my mother as I attempted to take him to school. I used to place him in the airing cupboard before bed so his green eyes would burn brightly in the dark to protect me from various under and over the bed monsters. I still remember hot tears burning my cheeks as one of the Meeks next door, (the family who shall inherit the earth at some point) whirled him around at high speed by his tail. Those tears were for Tiger’s pain, a somewhat misplaced feeling I realised while researching my children’s novel, The Mystery of the Missing Fur and more recently, its follow up The Macaw of Doom, which both feature two tigers, Mr Stipey and Marley.

As we kick off the Year of the Tiger, it’s shameful there are just 3,900 wild tigers left in the world compared to an estimated 8,000 in captivity in China and Asia and 10,000 in the USA.

I wanted to discover how we’ve reached this point, so I spoke to Simon Clinton, founder of a creatively led conservation organisation, Save Wild Tigers, who uses his marketing and advertising expertise and network, to raise awareness of the tigers’ plight.

“I actually grew up in Malaysia, home to the now critically endangered Malayan tiger. The tiger is the country’s national symbol and everything in that country is`tigerfied` from the national coat of arms, to their favourite beer, the biggest bank, and their national football team, so I’ve always been aware of wild tigers from an early age and the rich symbolism associated with the species across Asia,” said Simon,

Simon is a lifelong supporter of wildlife conservation, however two specific events conspired to create Save Wild Tigers 12 years ago. The first was being asked to do some work developing a TV ad for charity Born Free which his agency donated, where he met actor and conservationist Virginia McKenna of Born Free Foundation fame. Then, four weeks later coincidentally, he was asked to donate some of his creative agency’s time to celebrate the last Year of the Tiger with London cultural charity Asia House who planned to hold a tiger art exhibition. He agreed to help only if they donated some of the funds raised to tiger conservation charities. He organised a black-tie fundraiser, the `Save Wild Tigers Gala`. The rest is history, Save Wild Tigers was conceived.

“I became conscious about conservation organisations and individuals working with tigers and what a great job they were doing and are doing on the ground running conservation field programmes, but I soon realised there was a gap, indeed a real requirement to focus on raising awareness of the wild tigers’ plight and I could try to fill it by using my marketing and advertising background.

“Back in 2010 there was a real groundswell of public awareness about the poaching issues surrounding ivory and rhino but not about tigers. Tigers are universally loved yet very few people knew they were on the brink of extinction. For example, in Malaysia I spoke to politicians, media and indeed people from all sorts of backgrounds. I was shocked to find relatively low levels of awareness for the plight facing wild tigers in an actual tiger range country like Malaysia.

“So, we kicked off the Save Wild Tigers’ journey with the aim of creating lots of noise for tigers and indeed raising funds. However, our messaging strategy is very much to inspire the public and stakeholder into action through great creativity.”

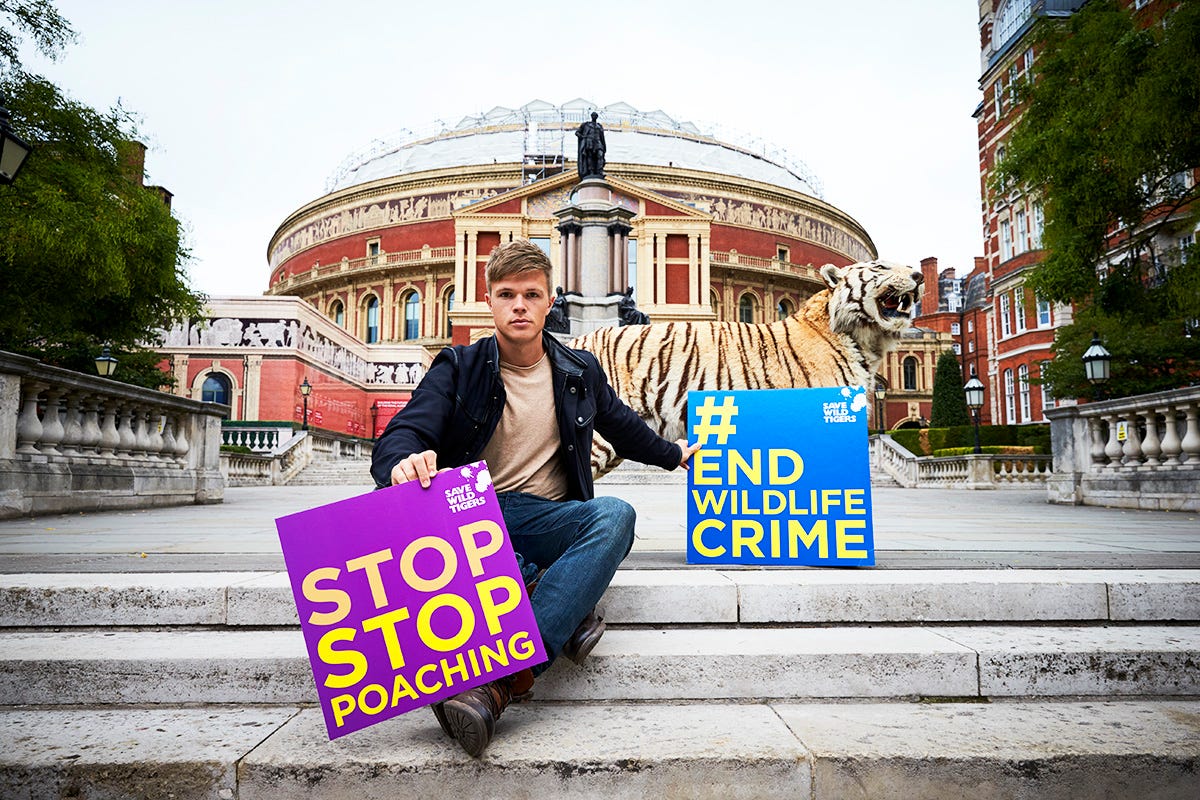

The organisation focuses on large scale campaigns to have the greatest possible impact on raising awareness of the bigger picture of wildlife crime and isn’t afraid to call out brands for using live tigers, often as aspirational props, in their advertising, something that Save Wild Tigers wants to make unacceptable as it fuels the image of tigers as a desirable consumer object.

Campaigns to date have included a one-month long tiger event taking over St Pancras International station creating the world’s largest ever Tiger event, re branding the station `Tiger Tracks` which included Brian May busking for half hour, the world’s largest wild tiger professional photographic exhibition at the Royal Albert Hall and a tiger-inspired art exhibition at the Café Royal. Just before the pandemic at the end of 2019, the outside of LVMH Belmond’s iconic Eastern & Oriental Express train was painted with an original tiger artwork created by British/Chinese artist Jacky Tsai, taking paying guests and influencer celebrities through tiger country from Bangkok to Singapore.

“All of these events have resulted in huge levels of global media pick up,” added Simon.

The Save Wild Tigers team have access to a wide range of artists, writers, actors, film directors and performers across all genres around the world who help spread the message, as well as their high-profile Save Wild Tigers ambassadors including Jaime Winstone, Jimmy Choo, Jacky Tsai, Mel Blatt, leadership expert Dr Amanda Goodall and Dan Olsen.

Over the years funds raised have gone to supporting these awareness campaigns and direct to conservation charity partners such as USA’s WildAid, WCS Malaysia, The EIA (Environmental Investigation Agency) and the Born Free Foundation to name a few. Organisations target the funds towards everything from anti-poaching patrols in Malaysia to getting rid of snares laid down by Vietnamese poachers and providing bio-gas stoves to Indian villagers as part of a campaign to reduce tiger-human conflict.

“We provide funding to the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) for major undercover investigations in Asia and China to identify criminal networks dealing in wildlife crime which goes hand in hand with people trafficking, drugs and arms dealing.

“There is some good news for wild tigers in that their numbers have increased from 3,200 at the last Year of the Tiger in 2010 to around 3,900 today. The increase is partly down to great conservation work over the past decade in India, Nepal and Bangladesh and Russia, home of the Amur tiger.

“However, over the same corresponding 10-year period tiger populations have declined dramatically across S E Asia and across the Indo China region. Indeed, over the past five years wild tigers have become extinct in Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos as a direct consequence of the poaching crisis across the region due to demand for skins, bones, and tiger products like tiger bone wine.

“In Indonesia, whilst poaching is still of great concern, habitat loss due to palm oil plantations is the biggest threat to the last Sumatran tigers.

“By focussing on tigers, we have the opportunity to reinforce the interconnected species and eco systems that will be directly impacted upon if we don’t succeed in preventing the extinction of the species, so in Sumatra the orangutan and Asian rhino. If we can help protect traditional tiger habitats and reduce wildlife crime, this clearly has a potentially positive knock on effect across other species and habitats.”

Another problem pushing wild tigers to the brink highlighted by Simon are China and Asia’s hideous tiger farms where, as the name implies, tigers are raised to be slaughtered for their skins and meat, bones for tiger wine and traditional Chinese ‘medicine’ (TCM) and teeth for necklaces, although officially its illegal in China to sell actual products containing any of these.

In TCM, tiger parts are used to ‘heal’ the liver and kidneys, to ‘cure’ epilepsy, baldness, toothaches, joint pain, boils, ulcers, nightmares, fevers, and headaches and ‘treat’ rat bites and laziness (of course) and prevent possession by evil demons (naturally) despite there being zero evidence tiger parts actually cure, heal or do anything except torture and kill tigers.

“The 8,000 tiger farms across China and Asia, often the back door to the illegal tiger trade, help create demand for tiger parts, such as skins for home décor, and directly drive the desire and demand for wild tiger parts and products, and hence fuel the poaching crisis.

“If we can’t save the most iconic species of all, what hope is there to save pangolins and other endangered and vulnerable species? It really is pretty damning in terms of the broader implications if tigers become extinct in the wild by the time of the next Year of the Tiger in 2034,” said Simon.

So how can we stop wild tigers’ extinction? Simon believes behavioural change will go a long way to helping in the medium to long term. A greater appreciation and value needs to be put onto the tiger alive than dead. Until the demand stops the killing will continue. TCM but, more importantly, the huge demand for often perceived aspirational tiger parts and related products for home décor and gifting are fuelling the demand for the tiger trade.

“However, in the short to medium term we need greater legislation and enforcement from CITES (a UN-style multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals) and from all tiger range country governments to ban tiger farming, dramatically upscale anti-criminal /poaching activities, including increase in prosecution capabilities, introduction of severe deterrent penalties and clear actionable plans for the protection of tiger habitats.”

Governments in these tiger range countries also need to be held accountable in developing and implementing short to long term tiger conservation programmes with quantifiable targets.

“We need to keep raising awareness and getting engagement across all stakeholders from government through to the general public in these tiger range countries so that local populations start to ask more questions and hold their governments and authorities to account,’ Simon explained.

“Based on current trends we may well have lost all tigers in the wild across S E Asia by the next year of the tiger in 2034 without a concerted effort. It’s a multi-pronged approach as there is no one remedy, no one conservation organisation, no one person but a combination of all, that will have the ultimate impact to save wild tigers, and of course a passionate belief that we can succeed.”

Tigers are everywhere in popular culture from Blake’s The Tyger to Judith Kerr’s The Tiger Who Came to Tea. They are the official symbol of Bangladesh, Malaysia, Burma/Myanmar, South Korea and Vietnam, ironically some of the countries where they are now extinct.

They’re used to sell petrol and a very sugary cereal, their stripes adorn everything from wallpaper to sofas and clothes, while their images are used so widely that if they had a pound for every tiger image or cuddly toy over the years, tigers would probably be far richer than a tech billionaire (and in a parallel world where they have opposable thumbs would be able to police their own protection and probably rule the world.) But the problem in this world of ours is we seem to worship these images over real wild tigers living in their natural habitats.

According to Chinese tradition, The Year of the Tiger is ‘all about making big changes and finding enthusiasm again, both for ourselves and for others. Everyone is fired up; generosity is at an all-time high and social progress feels possible again.’ Let’s hope this is the reality of the Year of the Tiger and we focus on the real wild tigers’ plight for once.

If you’d like to donate to Save Wild Tigers go to www.savewildtigers.org or other conservation charities working to protect wild tigers.