'Who's a trafficked boy then?'

Hello!

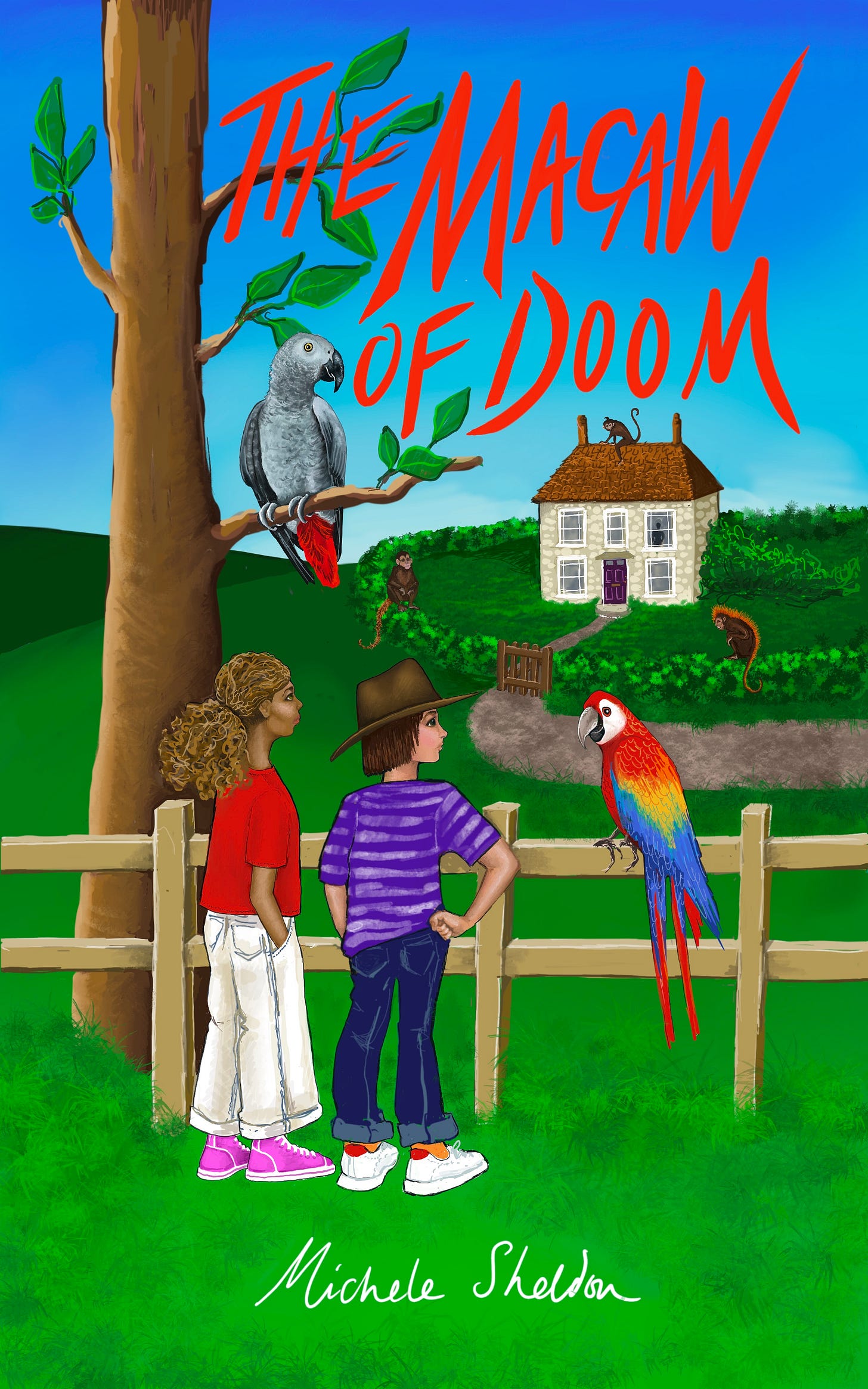

It’s three weeks until The Macaw of Doom is launched on World Parrot Day and I wanted to tell you what inspired me to write the follow up to The Mystery of the Missing Fur.

The book follows the adventures of Bernard and his best friend Larold after a supposed long-lost cousin turns up on their doorstep with Duke, a scarlet macaw, and later on, Jesse, a super intelligent African grey parrot.

Duke has been smuggled out of Brazil as an egg by one of the villains in the book and was inspired by the beautiful macaws I saw in captivity and in their natural habitats when travelling around Brazil. Jesse’s character came to me after researching the exotic bird trade and discovering the African grey claims the unenviable title of most trafficked, mostly to the Middle East and Asia, where they’re prized for their intelligence, mimicry skills and the fact they can live for 23 years.

He’s also partly inspired by a cockatiel we found in our garden hiding in some overgrown grass. We’re not sure where he blew in from but he soon acquired the name Charlie, and we grew very fond of him until the fateful day a certain someone in our family (not me, honest) let him out to stretch his wings on a very blustery day. Suffice to say we never saw him again. I hope he got blown onto another welcoming home. But I’ve never forgotten how sociable and affectionate he was, dancing up and down shoulders and chatting away, perhaps berating us for kidnapping him while he’d been taking a break on his way home to Australia, who knows.

The overall bird smuggling theme was inspired by meeting a macaw egg thief in Brazil many years ago. The man, or rather his entitlement to take what he wanted from another country, never mind the consequences, has haunted me for many years. The middle-aged Swiss-German boasted how he strapped the eggs around his stomach on the plane from Rio to Paris to keep them warm and then sold the macaws for thousands of dollars in Europe. He said he wasn’t doing anything wrong because it wasn’t illegal.

Almost 15 years later in July 2007, the EU Commission thankfully banned wild bird imports into Europe, and according to The World Parrot Trust this stopped “two million live birds from being imported annually, and eliminated “the associated mortality of 50% or higher, sparing a further two million.”

However, despite the ban, I discovered the trade in exotic bird trafficking, both legal and illegal, is still alive and kicking (though many of those trafficked aren’t) and is worth billions of pounds today.

Around 21% of the African grey global population is believed to be harvested every year according to World Animal Protection (WAP).

In February 2019, The Independent reported on an undercover film showing poachers trapping African grey parrots using a bird as bait to lure others, who are then stuck to a broom handle with glue. Their feathers are hacked off with a machete to stop them escaping and, probably, flying for a very long time. The cruelty visited upon these clever birds is made all the more unbearable because they are said to have reasoning skills on a par with a four year old human.

The trade causes three in four African greys to suffocate or die of starvation or disease in transit and has caused a “catastrophic” drop in numbers, with up to three million poached over 40 years and a fall of up to 79 per cent in 50 years. In Ghana the population remains at 1 per cent of its original and in Togo they are now extinct.

If you want to read more about the African grey’s plight and how they’re trafficked around the world, there’s an excellent Day in the Life of an African Grey.

Scarlet macaws are widespread across central and south America from south-eastern Mexico to Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia, Venezuela and Brazil and are faring better than the African grey with numbers estimated between 20,000 to 50,000. However, they are increasingly under pressure by being hunted and having their habitats destroyed for farming and logging, and are only found in small clusters across these areas.

We learnt last week that rainforests were destroyed at a higher rate in 2021 than in any previous year, particularly in the Amazon, so lets hope scarlet macaws don’t become the next Lear’s macaw. The beautiful macaw named after Edward Lear, illustrator and writer of nonsense poems, numbered just 80 in 1983 and, though still pitifully low, thanks to a controlled, protected habitat in Brazil have increased to around 1,300 .

The Macaw of Doom is out on Tuesday, May 31 during half-term and I’m very excited to have a book launch/signing at Waterstones Ashford, Kent from 11am to 1pm. Everyone is very welcome!

Have a good day and thanks for reading.